Moses explains ways that make one unclean and how to remedy that. He begins with land animals. Though the term is translated “earth” in verse two, what follows makes it clear that he is referring to land animals. Much of what we read about dietary practices appears in Deuteronomy 14. These two sections differ beginning in verse thirty-one. Before we get ahead of ourselves, we’ll note that after land animals, he turns to those in the water, followed by those of the air, amphibians, reptiles, and insects. The prohibition of pork among the Israelites is somewhat unique to them. Archaeological evidence shows a smaller number of pork bones dating to the second millennium BC in the Eastern part of Canaan. This proves that the taboo was observed at least that early. In other parts of Canaan, pork bones are plentiful. Later, Isaiah would associate the consumption of pork with idolatry (Is. 66:17). These dietary laws make a statement about Israel within the created order. They separate themselves from everyone else by this. Connected to impurity is death (11:24). Since this isn’t the state in which God envisioned humanity, to contact such renders a person unclean. Concluding chapter eleven is a call to holiness. The term translated “to distinguish” in 11:47 is the term used in the creation account (Gen. 1:6–7). Also, the phrase, “according to its kind in this chapter is also used in the creation account. In the hierarchy of creation, Israelites were to divide themselves between the unclean and the clean.

The notion that the blood of childbirth was impure was widespread in antiquity. The Hittites and Greeks held the same belief. The loss of blood was associated with death. All in all, she is prohibited from sacred things and places for forty days. This number is doubled if she bears a daughter. There’s no rationale as to why that is. A better rendering of the offering she should bring should be “offense” and not “sin” (12:6). Moving on, leprosy is addressed in chapter thirteen in broad terms and not very specifically. The phrase “leprous sore” in 13:3 is, in more modern translations, rendered as a “skin blanch.” That’s to say a loss of pigmentation. Once more, there’s an association with death. The quarantining of a leprous person, or anyone unclean, was for medicinal purposes in the case of transmission. It also set apart death from life; uncleanness from cleanness.

Notice at the beginning of chapter fourteen that the leper has been put out of the camp (14:3). The life of a leper once declared as such was isolating in many ways. On the one hand, in the previous chapter, the leper was to cover their mouth and shout that they were unclean if another person came near them. Additionally, they were ostracized from society. This is another theme of exile: exile from Eden, the scapegoat sent into the desert, exile from the Promised Land, etc. Anytime you read about living water, it refers to running water, such as a river or stream. This water carried the blood, and, hence, impurity, away from the camp. The living bird sent to the open country mirrors the scapegoat in taking away the transgressions from the camp. The reason leprosy is associated with guilt is likely because it was thought of as a punishment for some transgression (cf. Num. 12:10–15; 2 Chron. 26:16–21). Once again, we see blood and oil used together in cleansing (14:17).

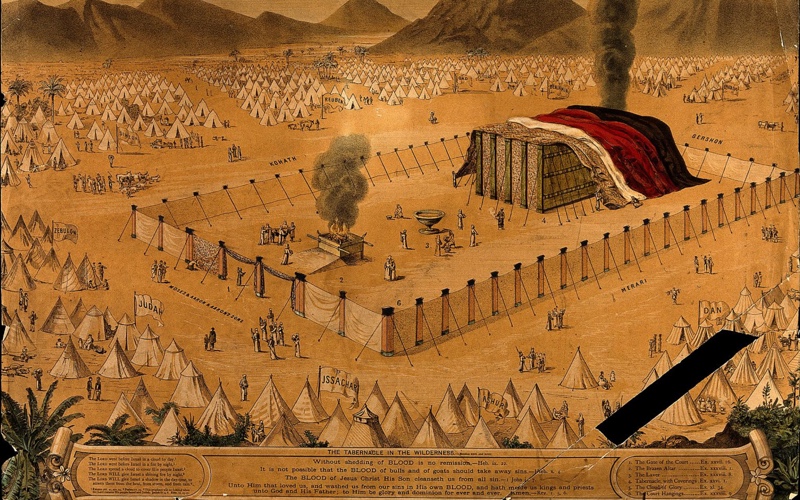

Chapter fifteen is primarily concerned with bodily discharges of various types. This can also be conveyed through secondary contact, as noted in verses four and nine. Once more in verse fifteen, an offense offering should be thought of rather than a sin offering. The contaminated person isn’t sinning by having this, but he is unclean because of it. While these instructions are primarily for Levites and priests, the whole point is to ensure they don’t enter the sacred space of the tabernacle in a way that would invite God’s wrath against them. This also extends to the average Israelite, who brings various sacrifices at the prescribed times.