John 1:19–34

John had previously immersed some Pharisees and Sadducees in the Jordan, but now priests and Levites came to him—inquiring who he was. One reason for the Levites’ arrival was that some expected the Messiah to be from the tribe of Levi. The book of 1 Maccabees reflects the longing for a Levitical kingly Messiah, and many expected him to be a priest. He, first, informs them that he isn’t the Messiah or Christ (1:20). Both terms mean “anointed” and were often used about leaders of Israel, especially kings. In Isaiah, Cyrus is called God’s anointed (Is. 45:1), so the title wasn’t limited to Jesus’ role. However, by this time, the word had taken on a meaning of the savior of Israel, God’s anointed one (cf. Ps. of Sol. 17:32). Elijah came to be associated with the figure because of Malachi 4:5–6. The belief was that either Elijah himself would return and be the messiah or someone like him, which was what John was. The prophet they expected was one like Moses (Deut. 18:15).

John was none of these, though he was the one like Elijah (Luke 1:17). John cites Isaiah 40:3 and Malachi 3:1 as an answer—he later tells people that he was to prepare the way of the Lord (John 3:28). Since John was none of the expected people, they ask why he was baptizing, likely because by so doing he was gathering disciples. John points them further to the one who is the come. He will come from among them, and it’s he who’s preferred over John.

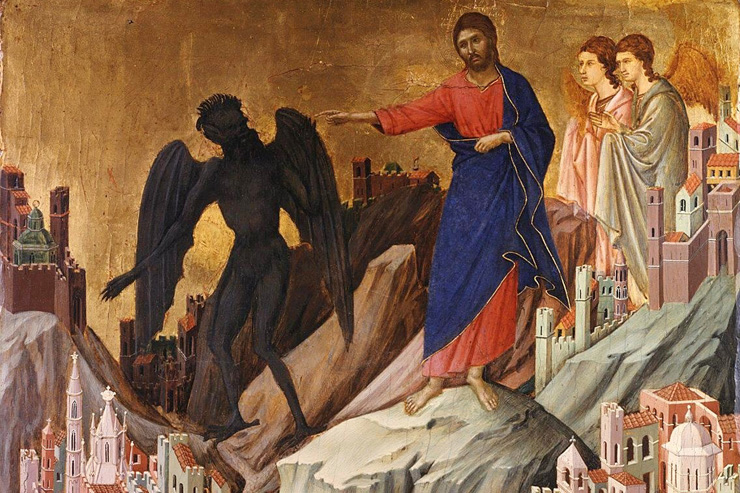

The next day, Jesus arrives at the Jordan—likely from his temptation. John proclaims Jesus to the crowd, and while his account doesn’t include the baptism of Jesus, it points out John’s response to it. While in the previous lesson, we discussed why Jesus was baptized, we see here that it was also for him to be revealed to Israel (v. 31). As we’ve also previously read, Jesus would be the one to baptize with the Spirit.

Several baptisms are mentioned in the New Testament: John’s baptism of repentance, baptism of fire, baptism for the dead (1 Cor. 15:9), baptism into Moses (1 Cor. 10:1–2), baptism of the Holy Spirit, and baptism in making disciples. Since only Jesus performs this, we have to look and see what exactly it is. Before he ascended into heaven, Jesus reiterated the promise (Acts 1:4–5), and we see it performed on Pentecost (Acts 2:32–33). There were only two examples in Scripture when this was applied: on Pentecost and Cornelius’ household (Acts 10:44–48; 11:15–18). This baptism enabled apostles to remember what they’d learned and be taught by God (John 14:26). They were also able to perform wonders and signs to accompany their preaching (Acts 2:43; cf. Heb. 2:3–4). Concerning Cornelius’ household, baptism with the Spirit was more to convince the Jews that Gentiles were worthy of salvation, too (Acts 10:44–48; 11:12). Moreover, it was God’s way of acknowledging the Gentiles, and the Jews’ understood that God makes no distinction (Acts 11:8–9).

Considering the numerous baptism we read about in the New Testament, we must establish a timeline because, by 64 CE, Paul wrote that there was only one baptism (Eph. 4:4–6). Jesus was crucified and ascended to heaven anywhere between 28–33 CE. We like to think that Jesus was born in 1 CE, but he was more than likely born between 4–6 BCE, given the dating of the death of Herod. Gentiles received the baptism of the Holy Spirit some 8–10 years later, putting us at 43 CE at the latest. This is important because by the time Paul wrote to the Ephesians, he stated that there was one baptism leading us to conclude that Holy Spirit baptism was no longer a factor. Just as John’s baptism was for a time and purpose (cf. Acts 19:1–7), so was Holy Spirit baptism. However, the immersion that makes us disciples of Jesus is universal and unending (Acts 2:38–39).