We must remember that when Jesus spoke about prayer, he urged that it be private and not as a show-off. He also adds that we shouldn’t presume that wordy prayers avail more than simple, concise prayers. In this context, Jesus gives his disciples a prayer to pray, something rabbis often gave their followers. Unlike our prayers today, there were and are liturgical prayers. These are prayers worded verbatim and not extemporaneously as we tend to do today. In synagogues, the shema is prayed on the Sabbath. This is the first word of Deuteronomy 6:4, “Here!” Jewish prayers are often named after the first word or words. The mi shebarach (“May the one who blessed”) has become increasingly common in synagogue meetings. The Lord’s Prayer would have been prayed verbatim. While modern Christians say it’s a model prayer to base our prayers on, the disciples would have repeated precisely these words.

Prayer is not a way to get God’s attention—we already have it. It is a way to express our feelings honestly and without reservation. Whether worry, anger, thanksgiving, or celebration, the Psalms reflect the various emotions expressed, from despair to joy, from repentance to gladness. Sometimes, the psalmist praises God above all that is, and at other times, lays blame at God’s feet. Prayer can strengthen our relationship with God just as any form of communication enhances a relationship. Muslims pray five times a day; Jews pray three times a day. Christians, however, have little to no discipline about prayer unless you’re in a specific branch that emphasizes it.

There are three versions of this prayer—Matthew’s, Luke’s (11:2–4), and one in Didache (ca. 50–60). In Luke’s version, the disciples ask Jesus to teach them how to pray. Didache is very similar to Matthew, with a few differences.

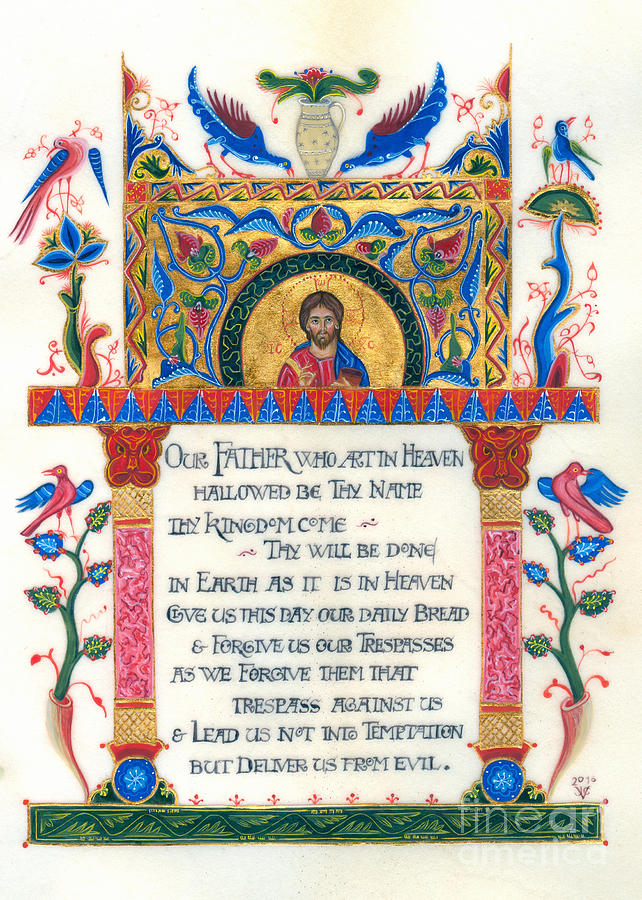

Our Father, who art in Heaven, hallowed be thy Name, thy Kingdom come, thy will be done, as in Heaven so also upon earth; give us today our daily bread, and forgive us our debt as we forgive our debtors, and lead us not into trial, but deliver us from the Evil One, for thine is the power and the glory for ever. Pray thus three times a day. (8:2–3)

The doxology at the end of Matthew’s version is a later addition. Interestingly, the earliest Greek and Latin manuscripts do not contain it. Even early church fathers knew of the shorter version. It makes you wonder why the doxology was added and kept in Matthew’s final version. Even a version of Luke contained, “May Your Holy Spirit come upon us and purify us,” instead of “Your kingdom come.” This is attested to by Marcion’s version of Luke (ca. 85–160); Gregory of Nyssa also wrote about this version. Several amulets have been found in Egypt on which the Lord’s Prayer was inscribed, so we see this prayer as transmitted through time.

Many Jewish prayers address God with formality, “Blessed be the Name of the LORD our G-d,” though not exclusively (cf. Mal. 2:10). Here, however, Jesus makes it intimate, addressing God as our father, denoting paternal love, protection, and provision. God alone is one’s father (Matt. 23:9). Saying that God was in heaven, the text says “heavens,” speaks about his ability to transcend the physical world. Jews at the time believed in three heavens (2 Cor. 12:2). The third commandment of the Torah was to not use the Lord’s name in vain (Exod. 20:7), and the wording in Exodus means to take a vow or oath in God’s name, as well as in casual conversation.

When Jesus prays for God’s kingdom to come, many say we should omit this portion of the prayer because the kingdom is already spoken of as something in the present tense (cf. Luke 9:27; 1 Cor. 15:23–25; Col. 1:13; Rev. 1:9). In this sense, I would agree; however, the kingdom has come in that God’s rule is on earth through the church. Yet, the fullness of his kingdom is to be realized after the judgment. Christians live in God’s kingdom, but there are still things on the earth, such as death, that occur that aren’t a part of God’s kingdom.

When we follow God’s will as we know it on earth, we may also see it done in heaven. We can learn this from the Scriptures that have been preserved for us. Jesus used those Scriptures to combat the devil in the wilderness. He also said he didn’t come to destroy the law and prophets but to fulfill them. The wording about daily bread isn’t as truthful to the text as many English translations give it. In Greek, “daily” isn’t expressed, but giving us tomorrow’s bread today is more accurate to the language. On the one hand, it envisions the messianic banquet (cf. Matt. 8:11). On the other, it reminds us that Jesus is our bread of life (John 6:35, 48, 51).

Sin is often regarded as a debt (cf. Matt 18:21–35; Luke 7:40–43). We accrue debts through our sins. These debts are too outstanding for our repayment, but the merciful God will forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors. If we practice canceling debts rather than calling in repayment, we will have our debts canceled (Matt. 6:14–15). When we think about temptation, we think of something that entices us to sin. The term translated as “temptation” refers to outward tests of all kinds. You could render the term “trials” or “ordeal.” These can lead to temptations, but they are not in and of themselves (cf. Prov. 30:7–9). Jesus’ hunger in the wilderness could have turned to sin had he succumbed to Satan’s temptation to turn stones into bread. Judas was not delivered from the evil one, mainly because he did not seek God’s will. Because of this, he opened himself to Satan (cf. Luke 22:3; John 13:27). Just as Satan tempted Jesus through his trial, he can use our ordeals to tempt us, giving that we become weak or despairing in them.