John Wesley was an Anglican priest who traveled to Georgia to evangelize the natives. While en route, the ship encountered a storm that threatened the lives of all souls aboard. Also aboard the vessel were Moravians. This church has its history in Bohemia and Moravia, the present-day Czech Republic (Czechia). In the mid-ninth century, two Greek Orthodox missionaries took the gospel to the area. They also translated Scripture into the people’s language. Still, in the centuries that followed, this area gradually fell under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Rome, leading some of the people to protest. John Hus, an admirer of John Wycliffe, led the charge a century before Martin Luther’s reformation. The Moravians were also going to Georgia at the behest of General Oglethorpe’s philanthropic endeavor. As the storm raged, Wesley became increasingly worried about himself. Meanwhile, the Moravians sang hymns throughout the storm, impressing Wesley. Given their calm and worshipful demeanor through the storm, Wesley was convinced that his faith wasn’t as strong as he believed and began to have a crisis of faith.

When John was at university, he joined a group his brother Charles and some friends founded. They covenanted to lead a holy and sober life, to take communion once per week, to be faithful in private devotions, to visit prisons regularly, and to spend time together each afternoon to study the Bible. John was the only ordained minister in the group, so he often took the lead. Outsiders mocked them as a “holy club” and “methodists.” The young priest doubts his faith in Georgia but keeps doing the work. He returned to England feeling adrift, so he contacted the Moravians, and Peter Boehler became his counselor. Boehler urged him to keep preaching the faith until he had it and to continue preaching once he had it. One night, he was with a group where Luther’s preface to Romans was being read. The reader spoke about the change that God works in the heart through faith in Jesus, and Wesley writes, “I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation: And an assurance was given me, that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.” The notion of having a “feeling” or warmness of heart is something that is seen at the Cane Ridge Meeting in 1801. In early America, and in the major denominations, one told of their “experience” and were then baptized and accepted as members. This is something that Alexander Campbell would later argue was unbiblical in conversion.

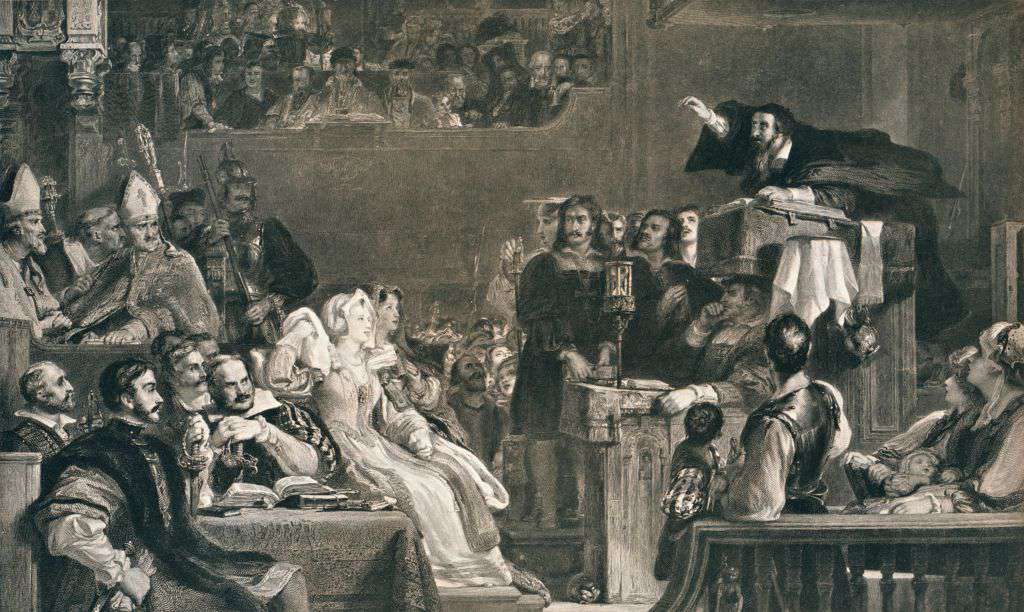

A fellow preacher of Wesley’s, George Whitefield, began preaching in a fiery manner. When he asked Wesley to fill in for him when he went to America, Wesley wasn’t as fiery a preacher as Whitefield. During his preaching, he noticed people moaning and weeping aloud. Others collapsed in anguish. Wesley was more suited to a solemn atmosphere, but he decided that such displays were a struggle between Satan and the Holy Spirit. Wesley was Arminian and not Calvinistic. Whitefield was the latter, so they parted ways, and Wesley remained an Anglican priest, holding meetings outside the worship of the Church of England that became dubbed Methodist. His Methodist meetings were meant to prepare people for Anglican worship and communion.

Wesley didn’t intend to establish another church, but his followers were organized into societies that met in private homes until they required a building. As the movement grew, they were divided into classes that had eleven members and a leader. They met weekly to read Scripture, pray, discuss religious matters, and collect funds. To be a leader, one didn’t need to have the credentials of an Anglican priest, so it allowed people to serve who otherwise felt unequipped in Anglicanism. However, a few Anglican priests joined over time. Lay preachers became familiar and were seen as God’s answer to the movement’s need for preachers. They didn’t replace clergy and couldn’t offer communion. Wesley held periodic meetings among the priests who had joined and the lay leaders, and this became the Annual Conference, where each was appointed to serve a circuit for three years. English law was changed to allow non-Anglican services and buildings, but they had to be registered. By doing so, it meant that they weren’t Anglican. Wesley reluctantly did so, taking the first legal step of creating a separate church. In the same way that Luther didn’t want to establish a new church but was forced to, so was Wesley.

After the Revolutionary War, Wesley wanted representatives in the United States, so he appointed Thomas Coke as superintendent—using the word translated as “bishop” for the role. He later sent Francis Asbury, a driving force in spreading Methodism westward into the American frontier. American Methodists became their church because they didn’t feel the need to follow Wesley, so the American church became the Methodist Episcopal Church. Coke and Asbury began calling themselves bishops, contrary to Wesley’s use of “superintendent.” This group merged with the Evangelical United Brethren Church in 1968 to form the United Methodist Church. The Evangelical United Brethren Church rose around the same time as the Methodist Church did in the United States. It was primarily made up of Germans who immigrated to the colonies. Its two heads were Philip William Otterbein (German–Reformed) and Martin Boehm (Mennonite), so two other denominations had united to form the Evangelical United Brethren Church.

In recent years, the United Methodist Church has split primarily over LGBTQ+ rights. Whether or not to ordain gay clergy and perform same-sex marriages has caused a divide, with many churches buying out of the Methodist Conference. Since 2019, over 7,000 congregations have left the church. That’s about a quarter of all Methodist churches. The debate had been ongoing for a decade as to operating with “inclusion” as a part of their culture while homosexuality had not been congruent with their teachings. Some have remained Methodist but are now Global Methodists, adhering more to the teachings of John Wesley. Others have simply remained autonomous congregations, operating as they see fit.