Many Christians plan to read their Bibles through in a year. Typically, they begin at the beginning, and by the time they arrive at the latter part of Exodus, it becomes cumbersome. Then, once you get to Leviticus, you might find yourself a tad discouraged. Here’s another way to look at Leviticus.

A mother had instructed her son not to play in a particular part of the woods behind their house because it was occupied by a family of skunks. One day, however, the son decided to inspect this area to learn more about skunks, since his curiosity was too intense to resist. At first glance, they seemed like cats, but with specific coloring. He moved in to see if he could hold one, but the younger ones moved away as the father stood his ground. As skunks often will do to warn, the father walked on his two front feet, putting the rest of his body in the air, as if he were walking on his hands. The little boy thought the skunk was doing a trick, so he moved closer, and then the father lifted his tail, took aim, and sprayed the boy with the noxious odor to repel him.

The boy ran frantically home, coughing and choking over the stench. As he cried out for his mother, she came to the front porch, and as her beloved son approached, she caught a whiff of the skunk and knew what had happened. She commanded the boy to stop because she couldn’t tolerate the odor. She didn’t stop loving her son, but he wouldn’t come into the house smelling like that. So what did the mother do? She didn’t hate her son. She didn’t reject her son. She wanted to help him. She prepared one of their troughs with a solution made of laundry detergent, peroxide, and baking soda. She placed her son in the trough and scrubbed him till the smell was gone. Then, he was able to come into the house, sit in his mother’s lap, and be comforted. When we think about sin and its effect, it’s similar to this story. We have become tainted by sin and its odorous effect, so we can’t come into God’s presence. However, God doesn’t look at us with hatred and malice, but with compassion and grace. He prepares a solution for us so that our sins may be removed and we can come into His presence once more.

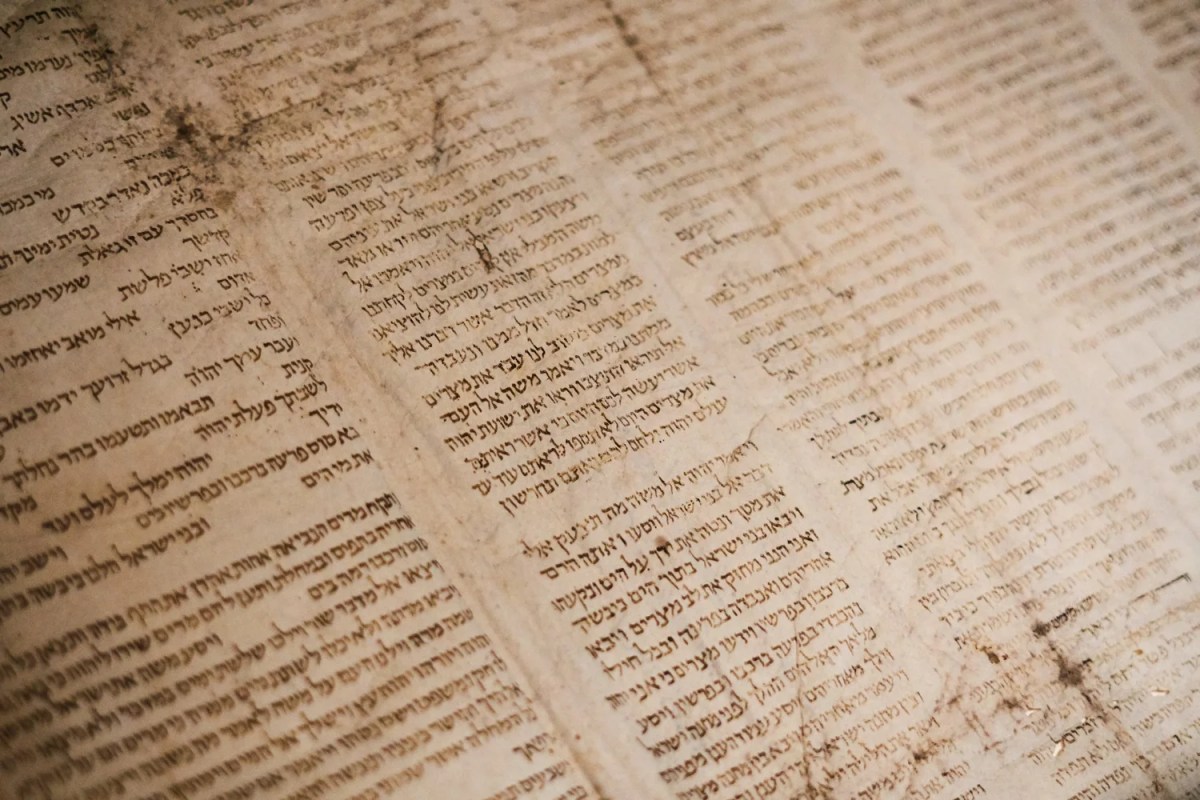

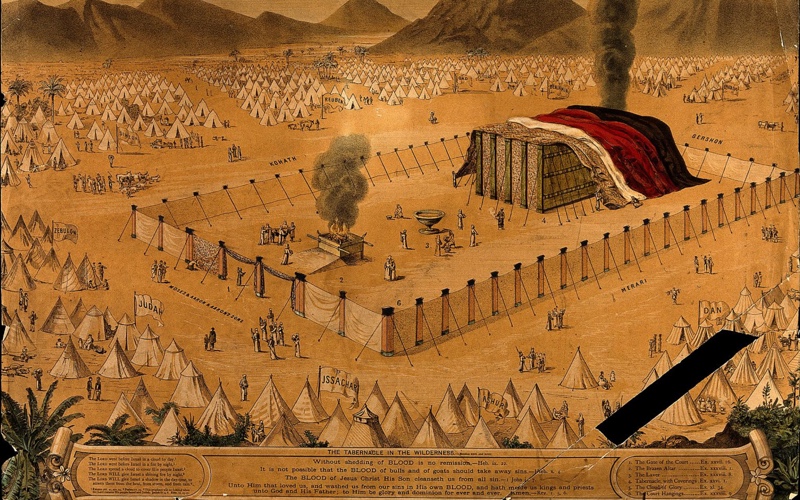

When God chose His special people, Israel, He wished to dwell among them. However, for Israel to live in God’s presence, God provided remedies by which He could dwell in their midst, and they could approach Him. This is what we read about in the book of Leviticus. What’s important to remember is the ending of Exodus, however, because it gives sense to the first verse of Leviticus.

Then the cloud covered the tabernacle of meeting, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle. And Moses was not able to enter the tabernacle of meeting, because the cloud rested above it, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle. Whenever the cloud was taken up from above the tabernacle, the children of Israel would go onward in all their journeys. But if the cloud was not taken up, then they did not journey till the day that it was taken up. For the cloud of the LORD was above the tabernacle by day, and fire was over it by night, in the sight of all the house of Israel, throughout all their journeys. (Exod. 40:34–38)

The glory—kavod literally means “weightiness”—of God is best thought of as a mantle of light enveloping God, and the cloud gave off the luminosity by day and appeared as fire by night.¹ When Moses first saw the Lord’s presence in the burning bush, he hid his face because he was afraid to look upon God (Exod. 3:6). Later, however, Moses’ faith in God had grown exponentially to the point that he wanted to see the glory of God. Still, he couldn’t see anything but the “goodness,” because seeing God’s face would have killed Moses (Exod. 33:18–23). Even then, God protected Moses from seeing Him.

After Moses communed with Yahweh, he came from Mt. Sinai with his face shining (Exod. 34:29–35). There’s a great lesson from this passage: The fear of Israel upon seeing Moses’ face parallels that of their fear of drawing near to God. Similarly, because Moses would cover his face with a veil when among Israel, this demonstrates that the holy of holies had to be partitioned off and enveloped in layers, yet accessible to the people.² Now, when we arrive at Leviticus, the question arises: “How can a people stained with sin live among the holiness of which they are afraid?” For the priests of Israel and the rituals prescribed in Leviticus, God provides in His mercy and grace the ways that He can be among a sinful people, and they dwell in His holy presence. It’s best to think of God’s holiness as the sun, which in its unadulterated form is powerful, and anything mortal that gets near it will burn up. The sun doesn’t hate such things but consumes them.

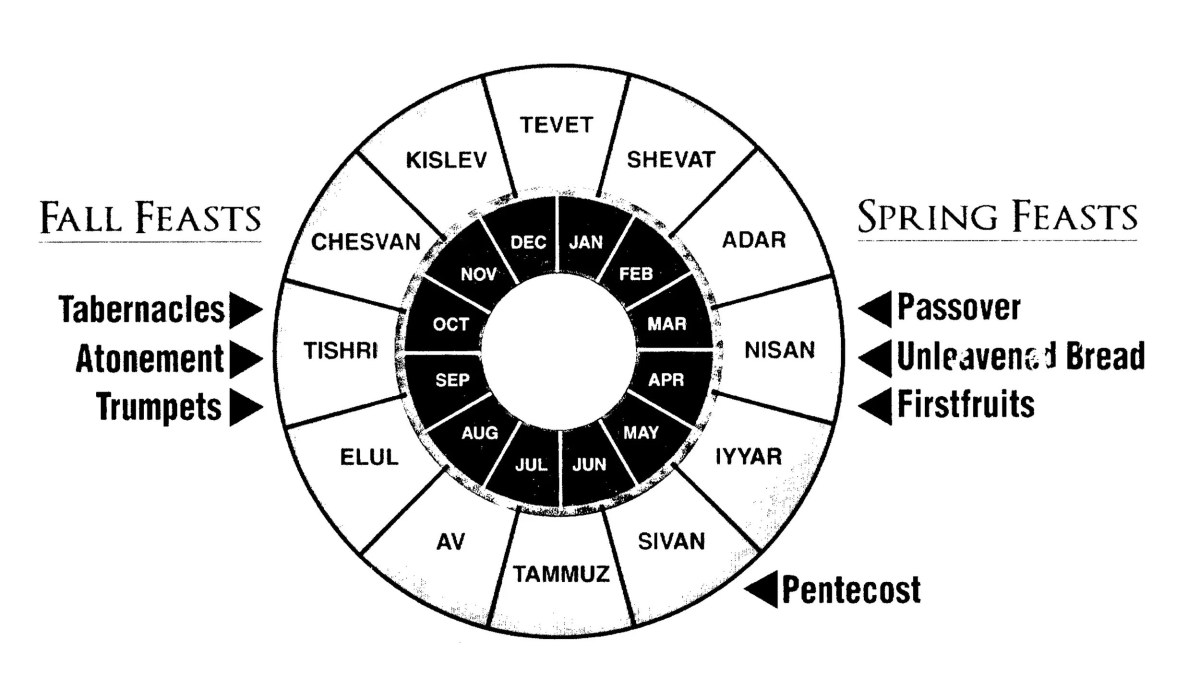

To outline Leviticus, we must identify its three major components: Sacrifices (Lev. 1–7, 23–37), Priests (Lev. 8–10, 21–22), and Purity (Lev. 11–15, 18–20). The sacrifices are ways to say “thank you” (i.e., grain and fellowship offerings) or “I’m sorry” (burnt, sin, and guilt offerings). Some of these occur on holy days when festivals were held. These were times of celebration to retell Israel’s history and explain why God chose them. Mediating these sacrifices were individual representatives who advocated for the people, called “priests.” These servants worked so closely to God’s presence that they were chosen to represent God to the people and the people to God. Such people were ordained and had to live by higher standards, similar to those of our pastors. Finally, the purity laws concerned cleanliness and uncleanliness. Cleanliness or purity is a state in which one can be in God’s presence, whereas the opposite is that of uncleanliness. Some of these concerned sexual relationships, social justice, and interpersonal relationships. These categories summarize the second-greatest command: to love your neighbor as yourself. Summing up the greatest commandment to love God with our whole being, we find that it includes dietary laws, skin diseases, dead bodies, and bodily fluids. Many of the latter three concerned life and death: one was sacred, and the others resulted from sin. Going before God in an impure state was inappropriate.

Tucked in the middle of the book is the Day of Atonement. On this day, the entire nation had sinned, perhaps unnoticed and unknown. The high priest would atone for the whole country by taking two goats and slaying one whose blood was brought to God’s presence to atone for the sins. God has said that the blood of a creature was life, so the life of the goat was to take the place of Israel and the penalty of their sin. The other goat was presented to the priest, who would lay his hand upon its head, confess the sins of the nation, and send the goat out into the wilderness, carrying the sins of the country away from them into the barren land. By this goat, God graciously removed Israel’s sins.

Christ became not only our high priest but did so while being tempted yet remaining pure (Heb. 4:14–16). As the high priest, not only offered the perfect offering but was Himself the offering so that He could go into the true holy of holies to minister for us (Heb. 9:11–14). What we learn from Leviticus only prepares us for the cross. Jesus Christ is now how we may live in the presence of the holy God.

¹ Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with a Commentary (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004), 535.

² Ibid., 513.