Many didn’t believe the church went far enough when England became Protestant. Those who read Scripture and applied it rather stringently were called Puritans. While some Puritans argued against episcopacy, others saw it as applicable but not divinely ordered. They argued for elders in each congregation; among those who argued for this, some believed congregations should be independent, and they were called Presbyterians. Baptists arose among the independents at the behest of an Anglican priest, John Smyth. Because of their views, they were persecuted by Mary Tudor, which led to their exile in Amsterdam.

While in Amsterdam, Smyth studied Scripture and determined that infant baptism was invalid, so he took a bucket and ladle and poured water over his head and that of his followers. The early custom of the Baptists wasn’t immersion but pouring over a believer’s head. Returning to England, they established the first Baptist Church in 1612. Two schools of thought arose between Baptists—many agreed with John Calvin’s doctrine of predestination. Others followed the belief of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected predestination and advocated that God had limited control concerning man’s freedom and response. These were called Arminians and were known as General Baptists. The other group was referred to as “Particular Baptists.”

Today, there are a variety of Baptist Churches.

- Independent Baptists are autonomous as opposed to Southern Baptists, who are primarily governed by the decisions of the Southern Baptist Convention. Those that aren’t independent send a percentage of their funds to a general fund overseen by the convention or association to which it belongs. The convention determines the financial and spiritual priorities of the congregations under their umbrella.

- Primitive Baptists are largely Calvinist and can somewhat resemble Pentecostals. They trust the Spirit to move in their worship, which can take a person anywhere. There is a Pentecostal Free Will Baptist church that believes in free will. Then again, there are Free Will Baptist Churches, too.

- Seven-Day Baptists hold the Sabbath as sacred and binding. This type of Baptist Church was first established in America in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1671.

- Missionary Baptist Churches focus on evangelism and helping the local community.

- Baptist Churches that are called “First Baptist Church” are to suggest that they were the first in the town or community.

- There are more than 65 Baptist denominations, but the majority belong to just five.

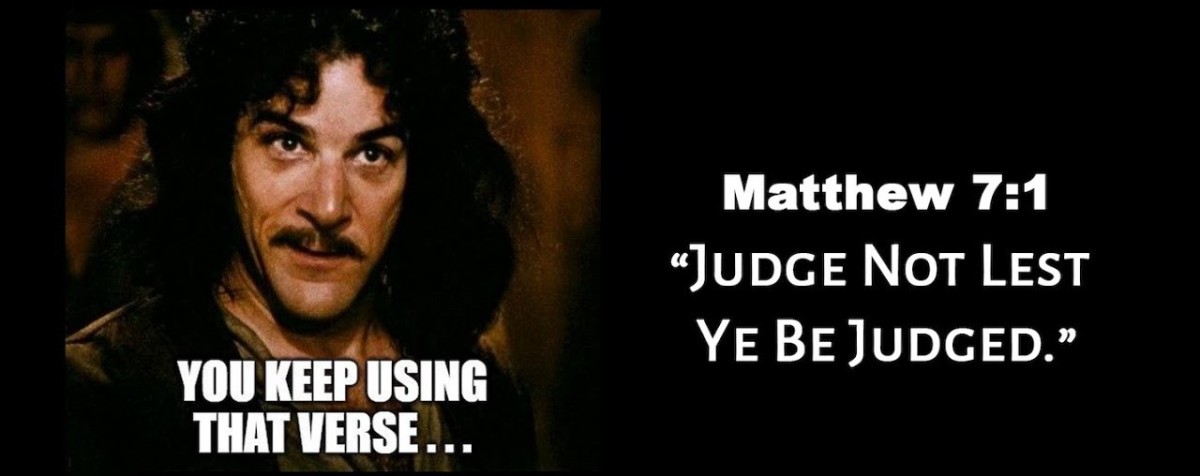

Many churches have eliminated denominational titles because they indicate division and the bad press associated with things that have occurred. One of the hallmarks of many evangelical groups, with which Baptists are often associated, is the sinner’s prayer. In 2012, David Platt, a Baptist minister, criticized the sinner’s prayer as unbiblical and superstitious.

Thomas Kidd informs that Anglo-American Puritans and evangelicals used the phrase “receive Christ into your heart” in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The phrase became more formalized during the nineteenth-century missionary movement and was a helpful way to explain that a person needed to make the personal decision to follow Jesus. This phrase’s commonality rose in the 1970s. Kidd also notes that George Whitefield published a hymn called “A Sinner’s Prayer.”

God of my salvation, hear, and help me believe:

Simply would I now draw near, thy blessings to receive.

Full of guilt, alas I am, but to thy wounds for refuge flee;

Friend of sinners, spotless lamb, they blood was shed for me.

One thing they believe that’s a significant divergence from us is that you can be saved before baptism. Also, they don’t partake in the Lord’s Supper weekly and use instruments. On this last point, this development is only 200 years old. Even some of their number opposed instruments.

“I would just as soon pray with machinery as to sing with machinery.” —Charles Spurgeon (Baptist) on Psalm 42

“Staunch old Baptists in former times would have as soon tolerated the Pope of Rome in their pulpits as an organ in their galleries. And yet the instrument has gradually found its way among them and their successors in church management, with nothing like the jars and difficulties which arose of old concerning the bass viol and smaller instrument of music.” —David Benedict (Baptist Historian) “Fifty Years among the Baptists”

Preceding Baptists, Mennonites, and Quakers was a group referred to as Anabaptists. As far back as the fifth century, when infant baptism was made the standard, as seen in the fifth Council of Carthage (ca. AD 401), dissidents who would be baptized as adults after being so as infants were called such. Their congregations grew and did well during the Roman Empire despite Catholicism persecuting them. Many were called Novatianists (third-century), Donatists (fourth-century), Albigenses, and Waldenses. Baptists often consider themselves inheritors of this history.