I grew up a fan of wrestling, or “wraslin” as it’s pronounced in the South. When I think about the Four Horsemen, I envision Ric Flair, Arn Anderson, Ole Anderson, and Tully Blanchard. However, as popular as the image is of Four Horsemen, it has nothing to do with wrestling, but with the Apocalypse of John. Remember that in the hand of God was a scroll sealed with seven seals (Rev. 5:1). This scroll would have somewhat been reminiscent of the Torah scroll unraveled in the synagogue service, from which the Word of God was read and an explanation given. In heaven, this scroll contains the message of the future relevant to the Christians in Asia. In the ancient world, a scroll that was sealed often held the impression of the one who wrote the message. Depending on who that was determined who was capable of opening the document. Here, only one person is found worthy to open the scroll and loose its seals—the Lamb of God, Jesus Christ, our Savior (Rev. 5:2–5). Only He could approach the God of heaven, take the scroll from His hand, and loose the seals.

The Messages of the Seals

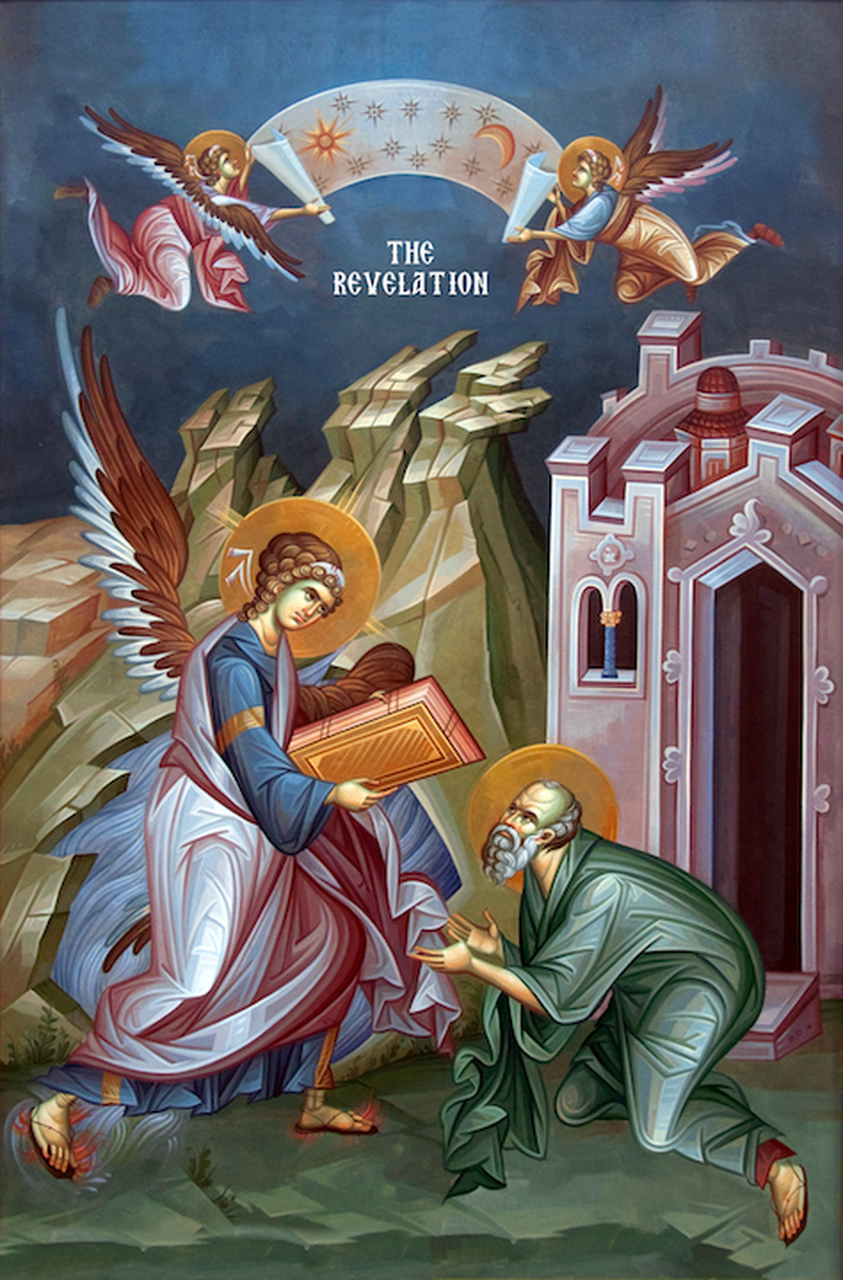

The vision of the four horsemen derives from Zechariah 1:8–11 and 6:1–8. In Zechariah, the horsemen are angelic creatures who report to the Lord regarding the state of affairs among the nations. Their coloring indicated the different countries to whom they were sent. In the Revelation, they are images of judgment posted throughout all the earth.[1] The first horseman represents warfare, and this as a judgment of God, we must remember (Rev. 6:2). The second, bloodshed since that’s what results from war (Rev. 6:4). The third horseman represents the economic fallout as a result of war and bloodshed—rationing due to famine (Rev. 6:5–6). The fourth horseman is pale or ashen. The Greek term here is chloros from which we get “chlorine.” This is a rather grim image because this is the color a person appears to be shortly after death. If you’ve ever been with someone who’s just passed away, their eyes turn this ashen, green sort of color. Because war, bloodshed, and famine are kissing cousins, and because those who are slain or die due to war and bloodshed may be left exposed, disease and plague may follow (Rev. 6:7–8). This black horseman has given us the common expression, “Black Death” to mean the bubonic plague.[2]

Next, sadly, we see that even some saints were not immune. The altar of heaven has beneath it the souls of the martyrs (cf. Lev. 17:11). They are at this place because they sacrificed themselves for the sake of the confession of faith in Jesus as Lord, and this is also where priests poured the blood of sacrifices (Lev. 4:7, 18, 25, 34). This would have entailed those who died for the faith up until this point in time—Stephen (Acts 7:57–60), those who died at the hands of Paul before he was a Christian, James the brother of Christ (Acts 12:2), and Antipas (Rev. 2:13) among others. Their cry to God wasn’t new, but a lamentation from the psalms where the psalmist pleads with God as to how long they must endure (Ps. 13:1; 79:5). The martyrs wanted the vengeance of God on those who’d put them to death. This isn’t an unholy request. We Christians sometimes cry so much for forgiveness, which is right to do, that we forget that justice has its place too. There’s nothing at all wrong for invoking the Lord’s vengeance upon those who’ve done such horrible acts. In the absence of immediate retribution, the martyrs are given a white robe to rest, because more would, sadly, join them. The white robes given to them are garments of having overcome (Rev. 3:5), and they’re the same garments in which the twenty-four elders are clothed (Rev. 4:4).

The fifth seal’s anticipatory measure, as well as the sixth seal, may entail eschatological material. There seems to be a decreation before the great day of the wrath of the Lamb. However, is it for the vindication of what they then faced, or what all Christians would share in until the end? I confess to not knowing the answer because the Bible often uses such language to denote the punishment of God at the end of an era. However, I tend to view this more as an end-times language than I don’t, but history records several such issues even in the first century:

These afflictions were visited on the world that John knew. In AD 62 the Roman legions were defeated by the Parthians to the east, and there were shortages of food, such as those recorded in Acts … and Seutonius. In addition, there were earthquakes, such as those in Asia Minor itself in AD 60, volcanic eruptions, such as Vesuvius, civil war in Rome following the suicide of Nero in 68, and the war in Judea that culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70.[3]

Early commentators were evenly divided on the interpretation of parts of the book. For we who are so many centuries removed from then, in comparison to early church leaders, can’t expect to grasp what even they struggled with understanding.

The 144,000

According to Jewish thought, four winds stood at each corner of the compass. These winds could destroy a nation (Jer. 49:36) or bring new life (Ezek. 37:9). Zechariah portrays these winds as chariots pulled by different teams of horses, which leave the Lord’s presence and go out into all the earth (Zech. 6:5–7). Jesus taught that at His coming during the destruction of Jerusalem that the angels would gather the elect from the four winds (Matt. 24:31).

Ezekiel 9 sets the backdrop for the sealing of God’s faithful. This imagery of seven executioners is present in Babylonian literature as well. There they punish those having committed religious offenses as is the case here (Ezek. 9:4). The imagery of Ezekiel’s seven would have reminded the audience steeped in idolatry about impending punishment that comes from Yahweh. The mark of their forehead in Hebrew was the taw. This was the last character of the paleo-Hebrew alphabet, and it looked like a modern “X” or cross.

Moreover, the Greek letter “chi” was equivalent to taw and was the first letter in Christ’s name in Greek. The church father Origen (185–254 CE) wrote, “A third [person] one of those who believe in Christ, said the form of the Taw in the old [Hebrew] script resembles the cross, and it predicts the mark which is to be placed on the foreheads of Christians.” In Revelation, the seal separates God’s faithful from the faithless.

Pseudepigraphical writing called the Psalms of Solomon was composed in the first century BCE (it details Pompey’s capture of Jerusalem in 63 BCE), and it gives a little insight as well on the marking of God’s people: “For the mark of God is upon the righteous for salvation. Famine and sword and death shall be far from the righteous, for they shall pursue sinners and overtake them, and those who do lawlessness shall not escape the judgment of the Lord” (15:6–8). Sometimes branding in antiquity was also a sign of a slave (3 Macc. 2:29). In Christianity, sealing became symbolic. The Holy Spirit sealed the Asian churches (Eph. 1:13; 4:30). This wasn’t a physical mark, as some might think. It was a mark distinguishable only by God and His agents of wrath (cf. 2 Cor. 1:22), and it distinguished the faithful from the wicked (cf. 2 Tim. 2:19). This seal in Revelation is to protect God’s faithful, as in Ezekiel (Rev. 7:3).

This list in Revelation of the 12 tribes differs from other records (see Gen. 35:23–26; 49:3–27; Deut. 33:6–25): Reuben usually heads the list, but Judah does here likely because this is the tribe from whence Jesus, the lion of the tribe of Judah, came (Rev. 1:5; 5:5). John included Manasseh while omitting Ephraim and Dan (see 1 Kings 12:29–30). Since this group is spared divine wrath, but not human persecution, it may be that they are among those who complete the number of the slain souls under the altar (Rev. 6:9–11). These twelve tribes are used figuratively of Jewish Christians (James 1:1). Jewish Christians were predominant over the first decade of the early church. Staying with the Jewish identity, their being “firstfruits” (Rev. 14:4) was also well-founded as spoken of by the Jews (Jer. 2:3; Rom. 11:16; James 1:18). If this is talking about Jewish believers, the great multitude in Revelation 7:9ff were Gentile believers. This could also be a reference to the church—God’s new Israel (Gal. 6:16; cf. Gal. 3:7–9, 29). Whomever they were, they sang a new song described as the roar of rushing waters, a loud peal of thunder, and harpists playing their harp. No heavenly creature could learn this song because participation is limited to those redeemed from the earth (cf. 1 Peter 1:12; Eph. 3:10), which centered on redemption by the Lamb from the beast. They were “virgins” (cf. 2 Cor. 11:2) who were blameless (Rev. 14:4). This may mean that they maintained ritual purity before battle (Deut. 23:9–10; 1 Sam. 21:5; 2 Sam. 11:11). Later on, Babylon (Rome) is referred to as the mother of harlots (Rev. 17:3–5), and those who consort with her would have defiled themselves (cf. Rev. 2:22).

The final seal serves as a prelude to the seven trumpets which are to follow. One round of judgment has been explained, and those in first-century Asia would have understood these matters far better than we could have. Here, however, is the comfort for those Christians: God judges those who do evil. In a court of law here on earth, humans attempt to execute justice as best as fallible beings can. Lawyers build cases, and it is prosecuted and defended before a group of peers who determine what the best evidence is. They hand in their verdict based on the available information, and a judge passes sentencing if guilty, or releases the accused if innocent. In the courtroom of heaven, no case has to be made, and the only defense anyone can ever have is the blood of the Lamb. Jesus Christ defends those bought with His blood, but those who are not faithful to Christ will be prosecuted according to divine law for their deeds. There is no escaping. There is no putting off what will pass.

[1] Farley, Apocalypse, 82.

[2] Reardon, Revelation, 55.

[3] Ibid., 55–56.