Catholicism and Orthodoxy were the same for centuries, claiming to be the original church. A split came in the Great Schism in 1054. They share seven ecumenical councils and adhere to the decisions that are derived from them (kind of). However, the Roman Catholic church changed the Nicene Creed (AD 325) to add filioque (“the son”), which upended the doctrine of the Trinity. What changed was that the creed said the Holy Spirit came from God the Father, but by adding the filioque, it read that the Holy Spirit came from the Father and Son, thus making the Spirit subjective to both and lessening his standing in the Trinity. Orthodoxy does not acknowledge this change that was added in the Middle Ages (AD 589).

Roman Catholicism also added doctrines through the pope’s primacy: purgatory, immaculate conception, stigmata, and praying the rosary, among others. They differ on original sin. Catholicism teaches that every person born is tainted with the guilt of the sin of Adam. This is why they “baptize infants.” Actually, they sprinkle them. “Baptize” means to immerse, which they don’t do. There’s a Greek term for sprinkling seen in Hebrews concerning the blood of bulls and goats (Heb. 9:19-21). That term is rhantizo. Orthodoxy views original sin as having the proclivity to sin because we are all born in the flesh. Still, newborns are innocents who will someday act upon that proclivity and invite sin into their lives. They immerse infants for around forty days of life.

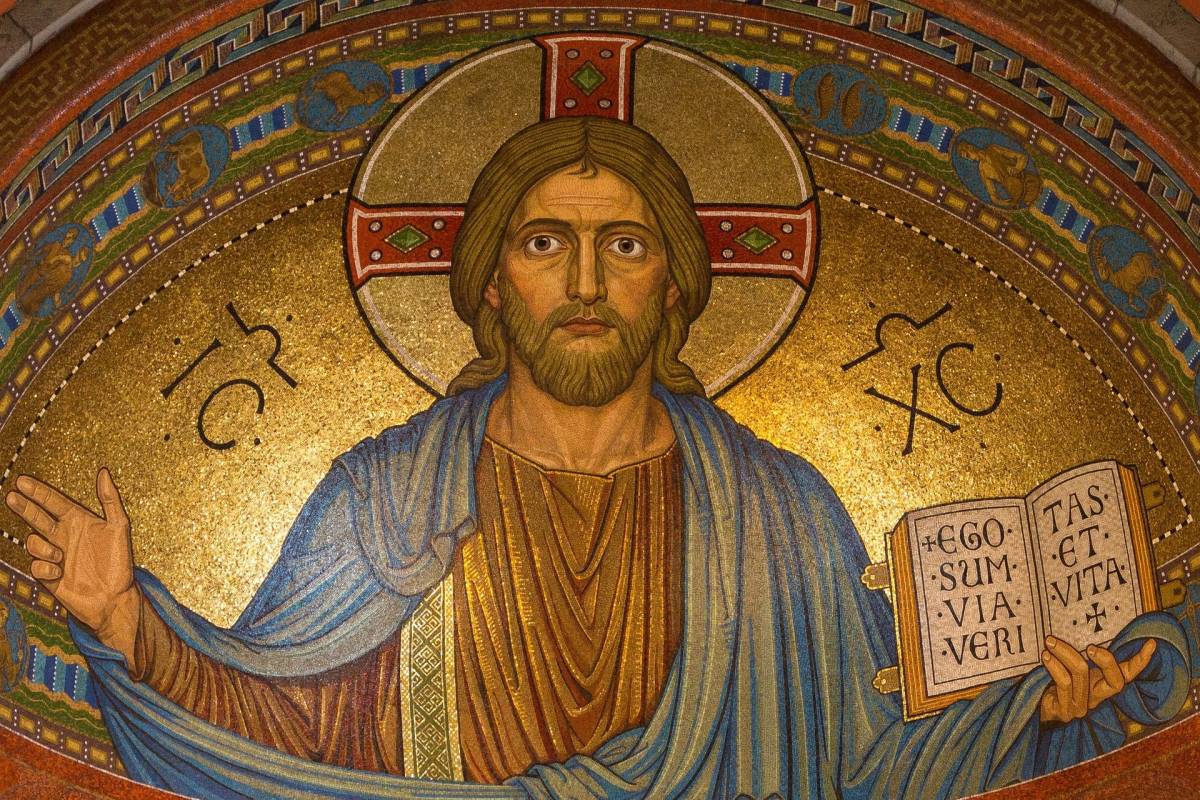

Ignatius of Antioch was the first to mention the catholic church (Smyrneans 8; ca. AD 107), and he did so as a call to unity around the congregational bishop who was to protect the church from heresy. The usage of “orthodox” was prevalent by the fourth century to distinguish those of the apostolic tradition from heretics. Here are changes that occurred that varied from apostolic teaching:

- In the early second century, the local congregation’s leadership went from elders, deacons, and ministers (1 Tim. 3) to one elder being chosen as bishop among his fellow elders. Jerome later regarded this change as a “result of tradition, and not by the fact of a particular institution by the Lord” (Comm. Titus 1.7; cf. Did. 15.1; 1 Clement 42.4; Poly., Phil. 5-6; Shep. Herm. vis. 8.3). This bishop was over the elders, deacons, and congregation. At times, you couldn’t take the Lord’s Supper unless the bishop was present to preside over it unless he appointed a proxy in his absence from among the elders. More and more became tied to the bishop, so he performed baptisms exclusively (see Ignatius, Mag. 2; Trall. 2; Smyrn. 8).

- The Protoevangelium of James is a second-century apocryphal Christian text, considered to be an “infancy gospel,” that narrates the birth and early life of Mary, the mother of Jesus. It includes details not found in the canonical New Testament, most notably the idea of her perpetual virginity; it is believed to have been written sometime around the mid-2nd century. This is the earliest evidence of special attention given to Mary, which would give rise to the practice of venerating her.

- By the third century, Cyprian of Carthage (ca. AD 200–258) wrote about baptizing infants as a passing matter (Epistle 58; cf. Acts 8:12, 36–37; 16:29–33), which suggests the practice was entirely common by his time. Discussions of the matter appear as early as Irenaeus (ca. AD 120/140–200/203; Contra Haer. 2.22.4) and Tertullian (ca. AD 200; On Baptism 18).

- In the latter third century, veneration of martyrs on the anniversary of their deaths became common. For Origen (ca. 185–254), explicitly, veneration stood with Jesus and not in competition with him (1 Tim. 2:5; cf. Lev. 19:31; Is. 8:19; Eccl. 9:5–6). In the fourth century, they were regarded as sancti, from which “saints” arose.

- The Council of Elvira imposed celibacy on clergy (canon 33; ca. AD 300–310), contrary to 1 Timothy 4:3.

- By AD 428, Pope Celestine rebuked bishops for not wearing distinguishing attire, which means clerical garbs arose sometime before then (cf. Matt. 23:5).

- Owing to their view of original sin, they celebrated Mary’s immaculate conception as early as the fifth century. This doctrine teaches that she was conceived without original sin so that she could bear Jesus. The doctrine was officially defined in 1854.

- The term “mass” appears around AD 604. It derives from the Latin term missa, meaning “to go.” It was pronounced at the end of worship and is closely associated with “mission.”

- In AD 595, the Patriarch of Constantinople, John the Faster, assumed the title “Ecumenical Patriarch.” Gregory the Great, or Pope Gregory I, wrote to the emperor, begging him not to acknowledge it. Emperor Maurice accepted it. A few years later, Emperor Maurice was slain by a usurper—Phocas. Pope Gregory sent letters of praise to the new emperor. However, in AD 606, Phocas transferred the title “Universal Bishop” to Boniface III, the bishop of Rome, thus establishing the modern-day Catholic Church of Rome.

- The doctrine of transubstantiation, elaborated by Scholastic theologians from the 13th to the 15th century, was incorporated into the documents of the Council of Trent (1545–63). This doctrine taught that when the priest blessed the bread and wine, it became the literal body and blood of Jesus.

- Papal infallibility was established in 1870.

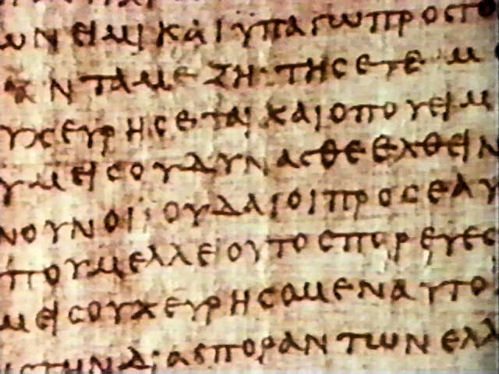

Perhaps the most significant difference between us is our views on Scripture. They contend that the church created the canon, thus exercising authority with and greater than Scripture. To them, the church is the proper interpreter of Scripture. I believe writings were already acknowledged as Scripture in the New Testament (2 Peter 3:15-16). Paul quoted Luke 10:7 in 1 Timothy 5:18. We also note that unanimity was taught in all the churches (1 Cor. 4:17; 7:17; 16:1). Also, New Testament writings were circulated among the churches (cf. Col. 4:16; 1 Thess. 5:27; 1 Peter 1:1; Rev. 1:4). Here are a few other factoids:

- Didache (AD 50–60) refers to the Lord’s Prayer as it appears in Matthew.

- The letter 1 Clement was written near AD 95, and he alludes to the writings of Paul as Scripture and Matthew, Luke, Acts, James, and 1 Peter.

- In AD 110, Ignatius alludes to Matthew, Luke, and John.

- Polycarp, in AD 110, called Ephesians Scripture. He also references Romans, 1 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 2 Thessalonians, and 1 & 2 Timothy; he quotes Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

I wouldn’t say the church created the New Testament. I would contend that they acknowledged and compiled the books identified as Scripture since the apostolic age. This was done as a reaction to proposed canons, some of which omitted the inspired books. This may have begun with Marcion, the second-century heretic who omitted all of the Old Testament and only recognized Luke’s gospel and some of Paul’s epistles as Scripture. In addition, we have Bryennios’ List, the Muratorian canon, Melito’s canon, Origen’s commentaries, and others. Many of these agree with minor variations, but they didn’t create them so much as to recognize what was a part of the apostolic tradition.