A lot of time was spent on the first eleven chapters of Genesis, but that all set us up to transition to Abraham. You’ll notice that from the beginning of Genesis until this point, God has selected individuals out of a group to represent Him in the fallen world. Adam and Eve were intended for this purpose, but they failed. Out of their two children, the good one was murdered for being good, and the murderer was further exiled from God. They bore another son through whom came Noah, and God hit the reset button on creation. Out of Noah’s sons, Shem would be the forefather of Terah, who’d have three sons, and out of those three sons, just like with Noah, one would be selected, Abraham.[1]

When we’re first introduced to Abraham, he goes by the name Abram (Gen. 11:26). He lives in Ur in Babylon, and our focus stays on him from here until he died in Genesis 25. Terah takes his family and leaves Ur, and they make it as far as Haran, some 600 miles northwest of Ur, where Terah dies. After his father’s death, Abram receives the call of Yahweh. They intended to make it to the land of Canaan (Gen. 11:31–32), but that didn’t happen. In these patriarchal times, the father, or head of the family, guided the family life. We know that Terah led the family in idolatry (Josh. 24:2). Still, we don’t understand why he left Ur and why they were headed to Canaan. However, this mirrors Israel in their later history because they would end up in Babylon because of idolatry, only to be allowed to return to the Promised Land, similarly to how their forefather traveled.

God wanted His first humans to be fruitful and multiply (Gen. 1:28), and God issued the same mandate to Noah (Gen. 9:1–3). The same request is made of Abram (Gen. 12:2; 15:5). Not only is this Israel’s story in a miniature form, but it’s also God trying to do what He intended to do from creation. In a world that’s fallen, God is redeeming it through one person, one family. “The Adam story looks forward to Israel’s story; the story of Abraham looks backward to creation.”[2]

No sooner than Abram arrives in the land God has promised to him, he leaves to go to Egypt because of a famine (Gen. 12:10). Sound familiar? This is the exact same trek Israel will follow for the same circumstance years later. Abram is concerned because his wife is beautiful, so he hands her over, and she is taken by the Egyptians. No worry, because Abram becomes rich in the process (Gen. 13:2–6). Yet, God plagues Pharaoh, and he sends Abram and Sarai off—just like He’d do for Israel. Abram and his nephew would settle apart from one another since their herds and flocks were too numerous. Lot would fall into enemy hands, forcing Abram to take his forces and retrieve him from captivity. Again, reminiscent of Israel and Egypt in a way.

After successfully retrieving Lot from bondage, Abram meets Melchizedek (“righteous king”), a king-priest of Salem, an early name for Jerusalem. This foreshadows the Davidic line from which Jesus came and the order He fulfilled. David himself somewhat fulfilled priestly roles and was also a priest-king in a sense. Much more could be written about this point, but it is an exciting study, to say the least.

Abram becomes concerned with how God will keep His promise. He proposes to God that he make an heir from his household, but God tells him that he will father a son (Gen. 15:3–4). To keep His promises, God binds Himself to Abram with an oath, a covenant (Gen. 15:9–21). This covenant’s meaning is that God will become the pieces of the sacrifices offered if He doesn’t come through with what He promised Abram. At the Exodus time, this was the promise invoked (Exod. 2:24–25).

All is well, right? Well, after some time, we’re not told how long Abram figures on helping God again. His wife, Sarai, offers her Egyptian slave, Hagar. Once the latter became pregnant, she despised her mistress, believing herself to have been elevated in status now. They have a tiff over this, and Hagar is sent away only to return after a divine revelation. Her son, Ishmael, will be a patriarch himself, and the Arabs claim descent from him (cf. Gen. 25:12–18).

A Turning Point in the Abrahamic Narrative

Let’s pause for a moment to remind ourselves how Abram has fared thus far. He has gone to the land only to leave because of famine. Talk about trusting in God, right? He lies and passes off his wife as his sister. The noble husband that he is. He returns to the land and has to divide from his nephew because their herdsmen aren’t getting along. He doesn’t want the problem to boil over into a family dispute. Good thinking here, at least. Since he’s not had children, he wants to name an heir from among his household servants, but God says, “No.” Then, after God makes a covenant with him, he goes on ahead to help God, at the behest of his wife, in keeping that promise by having a child with one of the maids. Still, that wasn’t what God had in mind, and, plus, it led to a family feud.

Between chapters sixteen and seventeen, thirteen years have passed. Ishmael is a gangly son that Abram has had the joy to watch grow up. Hagar has gone back to her place of being a submissive servant, and Sarai is happy. Yet, still no land and people. Out of nowhere, Yahweh shows up, commands that Abram walk before Him and be blameless. You kind of wonder whether or not that was an indictment of his early years of following God. Thus far, Abram has followed God for twenty-four years (cf. Gen. 12:4). Now, God commands that Abram have some skin in the game (pardon the pun). He commands circumcision (Gen. 17:9–13), likely a manner of God claiming the organ to indicate that Abram’s offspring was His and that Abram’s and Sarai’s future were in His hands. Anyone not circumcised, funny enough, would be cut off (Gen. 17:14). His (“Exalted Father”) and Sarai’s (“Princess”) names are both changed, akin to a monarch ascending the throne.

Abraham’s visited by angels who confirm Yahweh’s promise and even give him a timeline of one year (Gen. 18:10). The way it’s phrased, it was as if they said, “This time next year, I’ll return.” A condition of this promise is Abraham walking before God and being blameless, and this too is reiterated in Gen. 18:19. This time, however, Abraham is to examine God in a manner of self-discovery about himself as well as the character of Yahweh. Abraham is here and later depicted as a lawfully obedient follower of God (cf. Gen. 26:4–5), so the Israelite is simply following in his footsteps. Within the law are blessing (children) and curse (destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah). Whenever people act as depraved as those of Sodom and Gomorrah’s cities, they have nothing but to be cursed and incur God’s wrath for the pain they cause.

The promised, anticipated son is finally born. Abraham and Sarah had waited for this moment for so long, and now it had finally came to pass. After a couple of years or so, Isaac is weaned, and a big celebration follows. Sadly, the festival would turn to a wake because Sarah would finally have Hagar and Ishmael banished. Abraham isn’t thrilled about it, but God tells him to listen to her because the promise would be fulfilled in Isaac. Oh, and God would take care of Ishmael too.

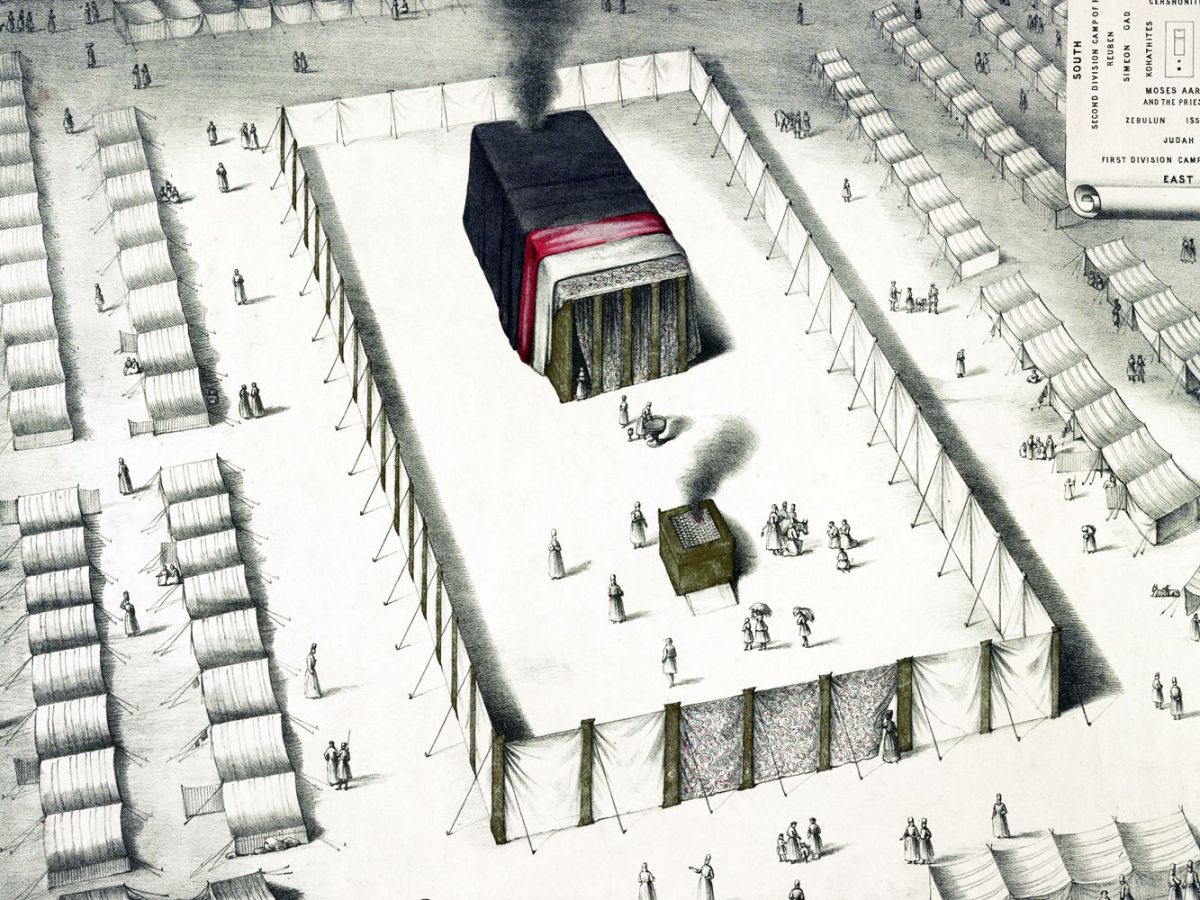

Several, perhaps many, years later, God asks the impossible of Abraham—to sacrifice Isaac. Critical to understanding this story is the laws regarding the firstborn. God says that the firstborn belongs to Him (Exod. 13:1, 11–13). That which opens the womb is God’s, and in the case of animals, we can accept this because sacrificing an animal to God was a part of the customs. God took the Levites to Himself, and they served in the tabernacle/temple, and for Isaac, he would be God’s too. Yet, God would make the exception in the case of humans. He wouldn’t accept human sacrifices because that’s what the pagans did (cf. 2 Kings 16:3). He would, however, take a substitute (Num. 8:17). We know the rest of the story, as Paul Harvey would say.

Abraham’s life points to the theme of God wishing to bless all peoples of the earth. He began with Adam, which was a bust, then through Seth, we’d find Noah, Shem, and Abraham. Abraham’s relationship with God is at times shaky. Still, overall he is the patriarch of the family of God in faith. He occupies many pages in the New Testament. To understand Abraham is to see the fulfillment of the promises God made over 4,000 years ago. In Abraham, we have that family through whom God promised to bless the earth in the flesh and in spirit. We are children of Abraham, who worship Jesus Christ, the Son of Yahweh.

[1] In case you hadn’t noticed, parents have a triad of children out of which one is selected. Adam and Eve bore Cain, Abel, and Seth, and Seth is selected. Enosh is named from Seth, and through him comes Noah, who also has three sons: Shem, Ham, and Japheth. Shem is from whom the Israelites would descend, and his lineage would go through Arphaxad to Terah who had three sons, Abram, Nahor, and Haran. Abram is selected, so the next logical sequence would be one son, and Abram’s one son out of two would be Isaac.

[2] Enns and Byas, Genesis for Normal People, 99.